Bad Dates

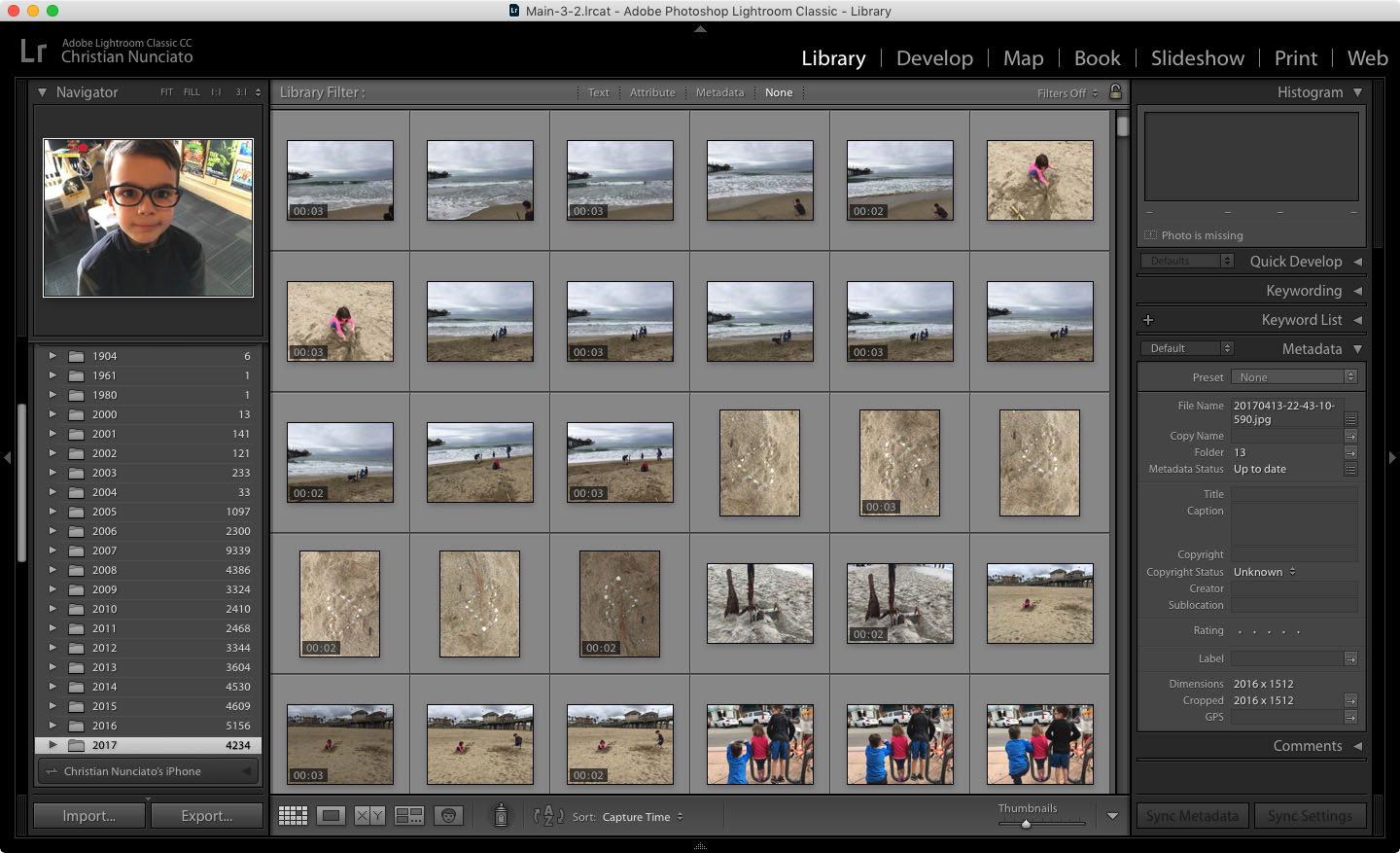

I’ve been a user of Adobe Lightroom for several years now, and I’ve generally been happy with it. While I’ve never been in love with the Lightroom interface — it works, but design-wise it’s a bit on the clunky side, and dated, and it often performs sluggishy even on my newish Macbook Pro — but it’s generally gotten the job done, and there aren’t, even in 2018, many photo-management apps that can handle tens of thousands of photos and videos.

I’m not the only one in my house who takes pictures anymore, either. My wife is a great photographer herself (she has a much better eye than I do, actually), and my kids are starting to get into it, too. So managing everyone’s photos, and making sure we all have access to them, has been a serious challenge for me over the years. I’ve thrown together many an awful hack, some involving external drives, some shared network drives, synchronization schemes, DropBox (nope), even dedicated computers, but nothing ever seemed to work, mainly because Lightroom operates as a window onto your filesystem: you can do just about anything you want with it, but your pictures have to be on your computer (or on a drive connected to it), which makes sharing your library with your scrapbooking wife an invariably awkward and frustrating process.

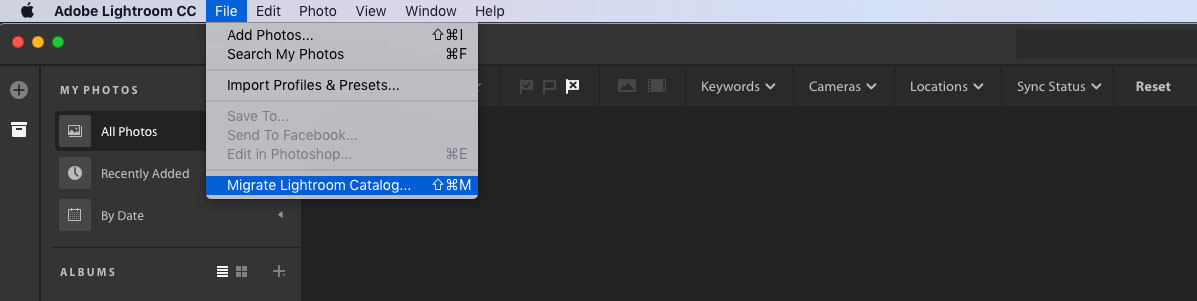

So when Adobe announced Lightroom CC, a cloud-based approach and ground-up rewrite of what’s now called Lightroom Classic, I was excited: it looked like we might finally be able to keep all of our photos (and videos!) in the Adobe cloud, and share them all easily between our Macs and our iPhones. I downloaded the app, fired it up, chose Migrate Lightroom Catalog, pointed it at my .lrcat, and let it run.

The import took a while, and when that was done, it took another couple of weeks to get everything uploaded and synchronized. But the result was glorious: not only was my entire library available on my laptop, but it was also synced magically to my phone, to the Lightroom website, and to my wife’s laptop and phone, tooI was thrilled. And since the Lightroom CC mobile app lets you choose to have all of your photos uploaded automatically, whatever my wife happened to shoot with her iPhone would show up moments later on my desktop, and vice-versa. As a software engineer who understands the complexity of this problem, I was (and remain) thoroughly impressed with Lightroom CC. It’s not perfect, and it’s certainly not free, but it’s by far the most sophisticated and complete solution out there today.

There was one little problem, though.

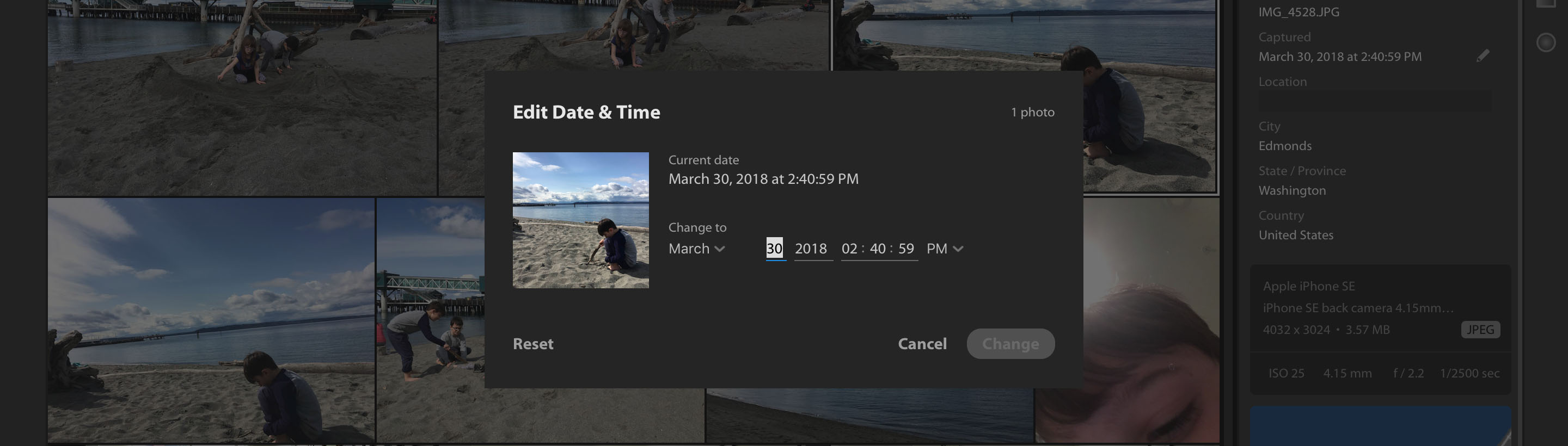

When the migration from Classic to CC had finished, I noticed a number of my pictures (some 9,500 of them, in fact) had been dropped into a bucket labeled No Datewhich was odd, considering that hadn’t been the case in Lightroom Classic, and irritating, given how date-oriented I am in my photography. (A bit of Googling led me to realize this is a fairly common problem.) The only remedy seemed to be tweaking the Capture Date manually, one photo at a time, using the controls in the UIwhich would’ve been fine, if there were only a few, but with close to ten thousand of them, I’d be at it for the better part of a week fixing them up, which seemed insane. There had to be a better way.

One of the nifty things about Lightroom Classic is that it uses a SQLite database to store everything about your photos, including their dates, which means, if you’re a geek like me (I love SQLite), you can get in there and run queries to fix these kinds of problems on your own. Lightroom CC appears to use SQLite also, but even if I could update its database manually (the schema is completely different), a number of the photos in the dateless batch really did seem to lack one or more EXIF dates; the right thing to do would be to update the files themselves and set their date fields properly.

So I came up with a plan, and with a little trial and error, it worked. Here’s what I did:

-

First, I exported all of the photos in the No Date bucket into a folder on my desktop called

Exports. The important thing here wasn’t the photos themselves, but their filenames. You’ll see why next. -

Then I wrote a little program to locate each of those files, using their filenames, in their original (i.e., Lightroom Classic-managed) locations, which for me happened to be on an external drive. The program would copy them into another folder on my desktop called

Originals, leaving me with two folders, side-by-side: one calledExports, the other calledOriginals. -

After checking to make sure the number of originals matched the number of exportsmeaning I had an original for every No Date exportI deleted the contents of the No Date bucket in Lightroom CC.

-

Then I ran another program called

exiftoolon each file in theOriginalsfolder, setting its EXIF capture date using the original file’s creation date. This might not work for everyone, but given my workflow, it happened to be a safe bet that the creation date would be pretty close to the actual capture date, so I went with it. -

Finally, with all of my

Originals now properly dated, I imported them into Lightroom CC.

That was itno more No Dates!

I’ll run through the steps in detail below, in case you happen to find yourself in this predicament, too. You’ll have to do a little Bash scripting to make this work, so I’m assuming you’re on a Mac (apologies to Windows users) and that you’re relatively comfortable on the command line.

Okay! Let’s make this work.

Step 1: Create Two Folders on Your Desktop

Pretty straightforward. Again, I named mine Exports and Originals.

Step 2: Export Your Dateless Photos

In Lightroom CC, click By Date, then scroll to the No Date folder and click it. Choose Edit » Select All, then File » Save To, then browse to your Exports folder and click Choose. Let the process finish — it’ll probably take a few minutes.

Step 3: Find Your Originals

Open a Terminal and make a new file on your desktop called find-originals.sh and make it executable:

$ cd ~/Desktop

$ touch find-originals.sh

$ chmod +x find-originals.sh

Then copy the following script into that file and save it:

for f in $1/*; do

exported="$(basename $f)"

# Locate the original

original="$(find $2 -name ${exported})"

# If the original isn't found, log it and continue;

# otherwise, copy it over

if [ -z "$original" ]; then

echo "Could not find a match for $exported"

else

echo "Found a match for $exported -- copying"

cp -vf "$original" $3/

fi

done

The script accepts three arguments:

- the path to your

Exportsfolder - the path to your Lightroom Classic originals

- the path to your

Originalsfolder

As I mentioned, I had exported my No Date files into a folder on my desktop called Exports. My originals were located on an external drive called Elements, and the empty destination folder, Originals, was on my desktop alongside Exports. So the command I ran was:

$ ./find-originals.sh \

/Users/cnunciato/Desktop/Exports \

/Volumes/Elements/Media/Lightroom \

/Users/cnunciato/Desktop/Originals

When that finally finished, I had about 9,500 files in Originals, which matched the number of images in the No Date bucket in Lightroom CC. I could now safely delete the bad ones.

Feel free to comment out the actual cp statement at first, just to make sure you’ve wired things up correctly. When you’re ready, run it for real. (We’re just copying, here, so don’t worry — all you have to lose is a little time and disk space, temporarily.)

Step 4: Kill All No-Dates

You can do it! After all, you still have your Lightroom Classic originals — and now copies of them, even — and you’ve verified the number of files in Originals matches the count of your No Dates in Lightroom CC. So go onselect all, Edit » Delete, and get ‘em outta there.

Well done.

Step 6: Write Out Some EXIF Dates

As I said, I was sure a good number of my photos really didn’t have EXIF dates (over a thousand of them were from an old Samsung flip-phone), and I wanted to fix that problem properly by modifying the files themselves, rather than just their Lightroom metadata.

There’s an amazing little command-line app called exiftool that’ll both tell you which files are lacking certain EXIF fields (e.g., dates) and also let you set their values, either “in place” (meaning on the source file itself) or, if you’re a little paranoid like me, on a copy of the file, preserving your original.

So I did this in two steps: first, I ran exiftool to find out how many dateless photos I had, and then I ran it for real to copy each file and burn a capture date into it. (I shoot a lot of video, too, and exiftool handles video formats, also — even the obscure ones from the early 2000s! It’s really great stuff.)

So assuming you’ve still got that same Terminal open on your desktop, run exiftool on your Originals folder to get a count of how many dateless images you’re dealing with:

$ exiftool -createdate -if 'not $datetimeoriginal or ($datetimeoriginal eq "0000:00:00 00:00:00")' ./Originals

This command asks exiftool to tell you which of the files in ./Originals is missing a datetimeoriginal value, which is what Lightroom considers a capture date. When you run it, you’ll get some output for each file, along with an aggregate result at the end. If, for example, I’d had three files in my Originals folder, two with dates and one without, my output might’ve looked something like this:

$ exiftool -createdate -if 'not $datetimeoriginal or ($datetimeoriginal eq "0000:00:00 00:00:00")' ./Originals

======== ./Originals/IMG_2949.PNG

1 directories scanned

2 files failed condition

1 image files read

Personally I find this output a little inscrutable, but I believe what it means is that two of those files have dates (i.e., they failed the -if condition of not $datetimeoriginal). If instead we’d gotten something like this:

1 directories scanned

3 files failed condition

0 image files read

… then we’d be done, as exiftool would be telling us that all of our files actually have capture dates. In my case, though, I had around 3,000 without them, so I decided to go ahead and update them all.

To do that yourself, run:

exiftool -P -O ./Output/ '-datetimeoriginal<filemodifydate' -if '(not $datetimeoriginal or ($datetimeoriginal eq "0000:00:00 00:00:00"))' .

This is essentially the same command you ran above, but with some additional options instructing exiftool to do some stuff:

-Pmeans “preserve my originals”-O ./Output/means “put the modified copies into the./Output/directory”'-datetimeoriginal<filemodifydate'means “set the capture date using the date the file was last modified” (which for me was also the date it was created)

If you’d like to use a different algorithm for setting your own EXIF capture dates (or even just learn more about what this awesome little program can do for you), check out the exiftool docs.

Once this was finishedit ran surprisingly quickly, considering how many photos I was processingI imported a few into Lightroom CC just to make sure things looked right. When they did, I imported them all.

Step 7: Re-Import!

The hard part’s done. Now, just choose File » Add Photos, browse to your newly populated Output folder, and click Review for Import. If things look good, click that shiny Add Photos button, then sit back and watch the magic happen.

Step 8: Celebrate

Well done! With any luck, once Step 7 completes, that No Date folder should be a thing of the past. If that’s the case, go ahead and delete everything we created from your Desktop. You’re done.

I’m sure I’ll write more about Lightroom in general; while I’m definitely a CC convert now, I still use Classic to manage my kids’ catalogs (they each have their ownthey shoot way too many pictures of absolutely nothing), and the CC software is continually evolving, which is awesome (and yes, occasionally frustrating). Nothing is perfect, but man, I have to say — on the whole, glitches and all, I’m still really impressed, and stoked that we’ve finally found system that works pretty much seamlessly for us.